Today, the average weekly screen time for an American adult – brace yourself this is not a typo – is 74 hours (and still going up).

#Neil postman amusing ourselves to death plus#

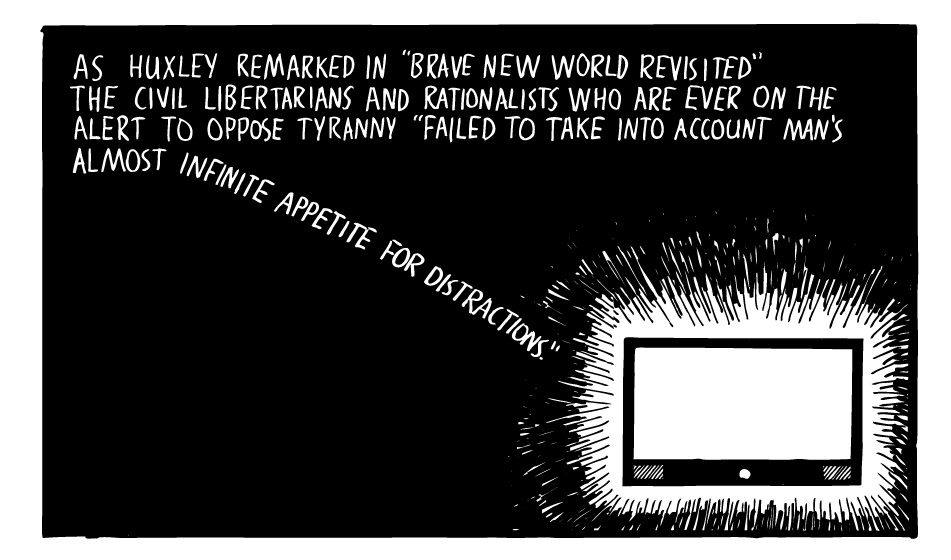

One-third of a century later, we all carry our own personalized screens on us, at all times, and rather than seven broadcast channels plus a smattering of cable, we have a virtual infinity of options. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture.ġ984 – the year, not the novel – looks positively quaint now. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. This was, in spirit, the vision that Huxley predicted way back in 1931, the dystopia my father believed we should have been watching out for.

#Neil postman amusing ourselves to death tv#

The more TV we watched, the more we expected – and with our finger on the remote, the more we demanded – that not just our sitcoms and cop procedurals and other “junk TV” be entertaining but also our news and other issues of import. It either captures your attention or it doesn’t. (This was pre-truthiness, pre-“ alternative facts”.)īut an image? One never says a picture is true or false. As my father pointed out, a written sentence has a level of verifiability to it: it is true or not true – or, at the very least, we can have a meaningful discussion over its truth. It was that the audience was being conditioned to get its information faster, in a way that was less nuanced and, of course, image-based. (My father noted that USA Today, which launched in 1982 and featured colorized images, quick-glance lists and charts, and much shorter stories, was really a newspaper mimicking the look and feel of TV news.)īut it wasn’t simply the magnitude of TV exposure that was troubling. The nation increasingly got its “serious” information not from newspapers, which demand a level of deliberation and active engagement, but from television: Americans watched an average of 20 hours of TV a week. Our political discourse (if you could call it that) was day by day diminished to soundbites (“Where’s the beef?” and “I’m paying for this microphone” became two “gotcha” moments, apparently testifying to the speaker’s political formidableness). The president was a former actor and polished communicator.

Unfortunately, there remained a vision we Americans did need to guard against, one that was percolating right then, in the 1980s. Wherever else the terror had happened, we, at least, had not been visited by Orwellian nightmares.” “When the year came and the prophecy didn’t, thoughtful Americans sang softly in praise of themselves. “We were keeping our eye on 1984,” my father wrote. Two years later, the Soviet Union collapsed. Within a half-decade, the Berlin Wall came down. And, to put a bow on it, the actual year, 1984, was fast approaching when my father was writing his book, so we had Orwell’s powerful vision on the brain. The misplaced focus on Orwell was understandable: after all, for decades the cold war had made communism – as embodied by Nineteen Eighty-Four’s Big Brother – the prime existential threat to America and to the greatest of American virtues, freedom. The central argument of Amusing Ourselves is simple: there were two landmark dystopian novels written by brilliant British cultural critics – Brave New World by Aldous Huxley and Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell – and we Americans had mistakenly feared and obsessed over the vision portrayed in the latter book (an information-censoring, movement-restricting, individuality-emaciating state) rather than the former (a technology-sedating, consumption-engorging, instant-gratifying bubble). Colleagues and former students of my father, who taught at New York University for more than 40 years and who died in 2003, would now and then email or Facebook message me, after the latest Trumpian theatrics, wondering, “What would Neil think?” or noting glumly, “Your dad nailed it.”

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)